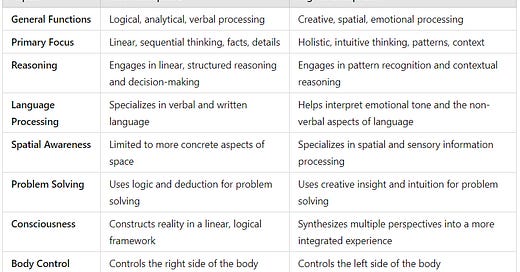

The brain’s two hemispheres are asymmetrical, each specialized for different functions, and the connection between them is surprisingly limited. This division reveals a deeper complexity of the human mind, where the left hemisphere typically governs analytical tasks such as language and logic, while the right hemisphere excels in creativity and spatial awareness. The asymmetry of the brain is not merely a random occurrence, but rather a purposeful design that enhances our cognitive and emotional abilities. The limited communication between the hemispheres is not a flaw but a way to allow each side to specialize and refine its role. This configuration suggests that the brain's duality contributes significantly to how we experience and interact with the world. Far from being a passive feature of the brain, this division actively shapes the way we process information and respond to stimuli. It allows for a dynamic interaction between different types of cognition, enabling us to simultaneously reason and feel, analyze and imagine, without one process being overly dominant or subordinated to the other.

The brain’s division into two hemispheres may serve a functional purpose, enhancing control and refining processes, rather than merely being a redundant or arbitrary feature. Each hemisphere operates with its unique set of cognitive tools, and their distinct functions are not just complementary but essential for the complexity of human experience. It is as though the division of the brain fine-tunes the processes of thought, enabling a deeper mastery over both our logical and emotional selves. This functional duality supports the notion that the brain, far from being a homogenous mass, is a finely tuned system, where each hemisphere refines its specialized function to contribute to a unified whole. This suggests that the very division of the brain is not a flaw in its design, but a necessity for optimizing our mental and emotional capabilities. It allows us to have clarity in our thoughts and depth in our feelings, holding space for both our intellect and our intuition to coexist in an intricate dance that informs every aspect of our being.

The corpus callosum, the structure connecting the hemispheres, allows communication but also inhibits one hemisphere from interfering with the other, highlighting the significance of division in brain function. This communication system is not simply an avenue for transmitting signals; it acts as a regulatory mechanism, ensuring that the hemispheres do not disrupt each other’s specialized tasks. In this delicate balance, the mind’s two poles—reason and intuition, intellect and emotion—remain distinct yet harmonized through the action of this connecting bridge. The corpus callosum ensures that the complexity of our thoughts and feelings can be integrated without one overwhelming the other. It allows each hemisphere to work within its designated territory, yet remain in constant dialogue with the other, enhancing both cognitive and emotional processing. This finely tuned regulatory system is one of the brain's many marvels, demonstrating that division itself is not inherently detrimental but is, in fact, necessary for the brain's sophisticated functioning.

The mind is not identical to the brain but is instead a process grounded in consciousness, which is itself unique and irreducible to any other form of experience. The mind’s nature transcends the brain's physical structure, suggesting that consciousness is a dynamic field of awareness that cannot be fully explained by neural processes alone. The mind, rooted in consciousness, is an ever-evolving process, independent of the brain’s physical existence, yet intricately related to it. This distinction between the mind and the brain invites us to consider the possibility that consciousness is not merely an emergent property of neural activity but may be a more fundamental aspect of reality. In this view, the brain functions as a physical organ that supports the mind, but the mind itself is a living, flowing process that cannot be wholly captured or limited by the brain’s material structure. Consciousness, therefore, becomes a kind of ground from which mental processes arise, yet it is not bound to the brain or reducible to its workings. This understanding invites us to look beyond the physical brain and explore the nature of the mind as something that exists beyond the confines of neural activity.

The brain and consciousness are deeply interwoven, but the certainty of consciousness being a product of the brain is debatable. The relationship between mind and matter remains an open question, influenced by the mind's capacity to create concepts, including that of the brain itself. Consciousness shapes and informs our understanding of the brain, challenging us to reconsider whether it arises from the brain or exists independently, influencing the brain’s development. The fact that we can conceptualize the brain itself through our consciousness suggests that the relationship between the two may not be as straightforward as many presume. Consciousness, in its fluidity, is capable of creating ideas and concepts that inform our understanding of the material world, including the brain. However, this very ability to conceptualize the brain leads us to question whether consciousness is a product of the brain or something that exists in its own right, influencing the brain’s structure and function. This question continues to be a deeply philosophical and scientific exploration, one that invites us to consider the limits of materialism and the vast potential of consciousness.

Dualism, such as Descartes' view of mind and body, cannot be reduced to simple "whatness," as the nature of consciousness involves both unity and profound disparity, suggesting that mind and body are not mere substances but complex, interacting processes. The mind and body exist not as separate entities but as interconnected aspects of a larger, fluid process. Consciousness reveals both a unity of experience and a diversity of states that cannot be captured by the simplistic view of mind as a separate substance from body. This recognition calls us to move beyond traditional dualism, which views mind and body as separate and fundamentally distinct substances. Instead, we are encouraged to see the body and mind as intricately interwoven, working together as parts of a whole. The nature of human experience is thus not captured by the simple categorization of mind versus body, but by the understanding that both are in constant dialogue, shaping and informing each other in ways that are complex, dynamic, and essential to our sense of self and reality.